This is a topic of interest to linguists and conlangers alike. Head directionality is up there with basic word order and morphosyntactic alignment as one of the most spooky, ethereal, yet ultimately most fundamentally defining characteristics of a given language, so it's important to be aware of when studying or creating one.

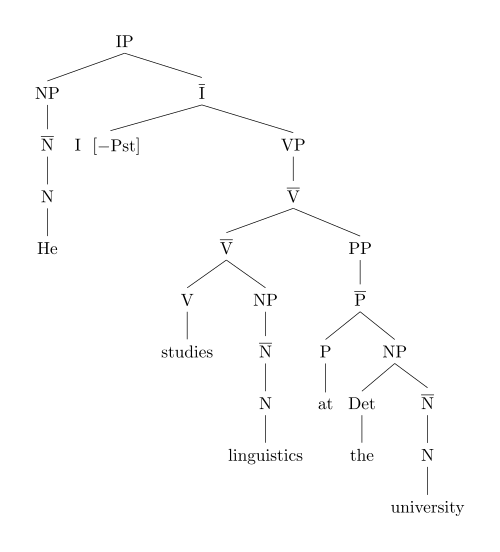

In X-bar theory, a widely-used model of sentence syntax, every sentence is a tree, composed of words and phrases hanging off one another in relationships between modified bits, called heads, and the things modifying them. Head directionality is a pretty opaque term that just refers to the order of syntactic heads and their respective modifiers. If this vague description didn't put much of an image in your head, I don't blame you. Here are some examples of head-modifier relationships (in all of these the modifier is listed first):

Object - Verb

Adverb - Verb

Semantic Verb - Auxiliary Verb

Noun - Adposition

Possessor - Possessee

Adjective - Noun

Relative Clause - Noun

Dependent Clause - Complementizer

Determiners like articles and noun classifiers might count as either a head or a modifier.

When we classify a language typologically by head directionality, we're just talking about whether it more often puts modifiers before or after their heads. So a head-final language would put together related pieces in the orders listed above, and a head-initial language would just always flip that order. Essentially no language will be entirely one or the other, and some languages have a balanced mixture of head-initial and head-final behaviors, but having strong tendencies towards one or the other is very common. Japanese is a frequently cited example of an almost entirely head-final language. Spanish is a good example of a very strongly head-initial language, although object pronouns and possessive pronouns come before their heads (as in yo lo veo, literally "I him see" or su abrigo, "his coat"). Interestingly, with full nouns in these syntactic roles the language reverts back to head-initial (yo veo Carlos or el abrigo de Carlos). This is part of the wider trend that "heavy" modifiers very commonly shift after their heads even if lighter modifiers come before.

Having a modifier come before its head is a strain on the listener's memory. Our language-wired brain is always thinking one step in advance and trying to predict the rest of the sentence - that's one of the reasons we're so fantastic at comprehending lightning-fast speech - but if we have a lot of modification to remember before finding out what the modified thing is, we can spend too much mental effort, or working memory, trying to predict and ultimately lose track of what's been said. For small modifiers this might not matter much - syntactic consistency is likely to outweigh the small memory tax - but the larger the modifier, the more likely it is to find its way to the end. This is especially true of relative clauses, whole clauses that describe a noun as in "the dress [that she wanted to wear to her sister's wedding]," which are some of the lengthiest modifiers out there and are especially likely to come after their head nouns even in languages otherwise expected to be head-final.

Further reading:

Head Directionality

X-bar Theory

WALS map of Genitive-Noun order

WALS map of Relative Clause-Noun order

Relative clauses and working memory

No comments:

Post a Comment